Part 2: The Impacts of Our Water Crisis

Can you imagine waking up one day and finding yourself without water in your home? Or even worse, can you imagine finding out that your well, the only water source your community has, went completely dry and collapsed onto itself? That’s exactly what happened to the community of El Fraile – a rural community of around 300 families less than an hour away from San Miguel de Allende that subsequently partnered with Caminos de Agua on a large-scale Rainwater Harvesting program. There is a tall and lengthy wall that divides the community of El Fraile, with an enormous agricultural field on one side – using up exorbitant amounts of water from the aquifer – and the people of the community living on the other side, whose well went completely dry as a direct result.

Unfortunately, El Fraile isn’t a rare example. This has become a reality for many communities across our watershed. Chip Swab, one of the sponsors of our Spring Match Campaign has witnessed similar situations firsthand through his volunteer work as a logistics coordinator at Feed the Hungry; in his own words:

"Well, there is this community called La Palma. When I first started going out there, they had a very old well, and it was clear that the water level had dropped quite a bit. They were using a burro (“donkey”) that they had tied to a rope. They dropped these big buckets down into the well, and the burro pulled it up full of water. One time, quite a while later, I was out that way again, and when I saw that there was no more rope, burro, or man – it was obvious… The well had collapsed and the community no longer had a source of water of any kind."

Photo: Child from the community of El Fraile looking at the agricultural field across the road that divides the community from such field.

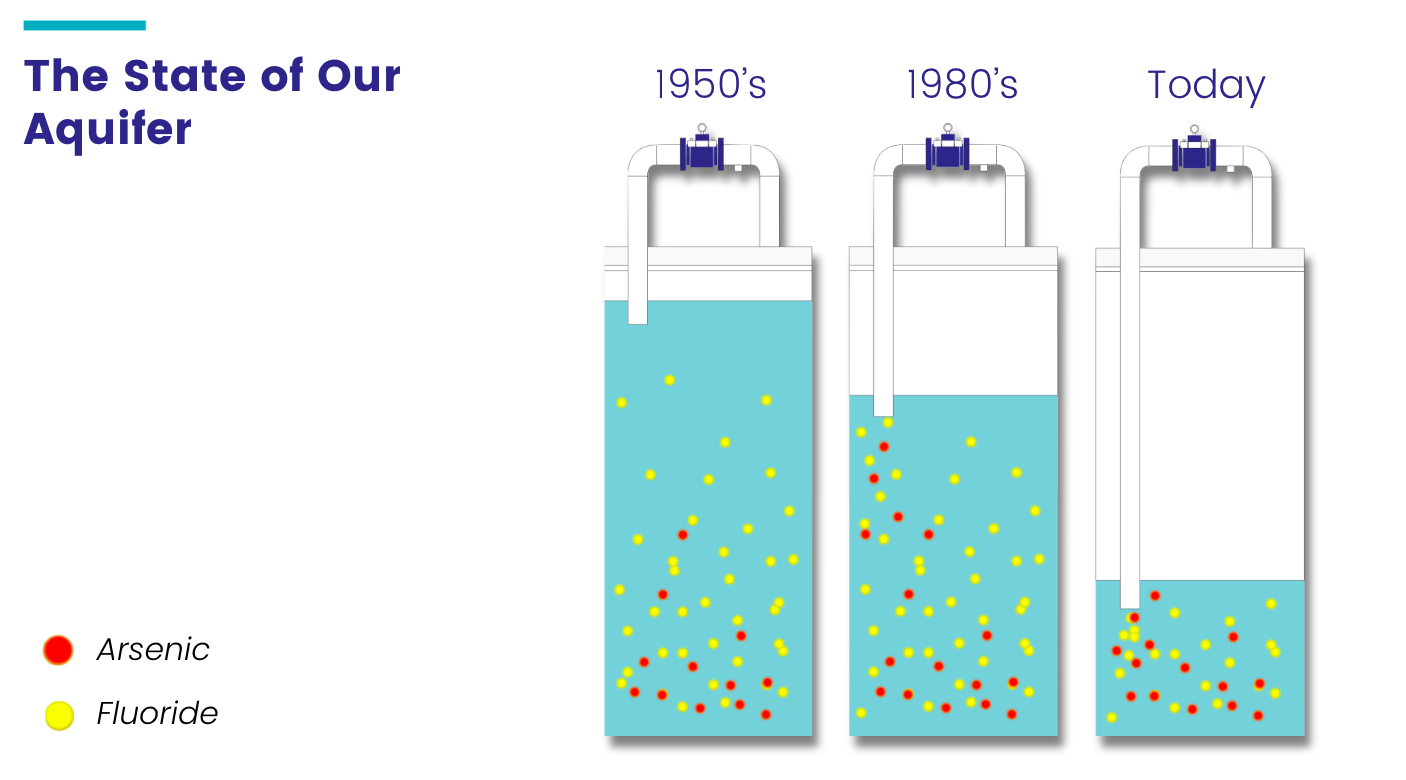

Water scarcity and water contamination are two sides of the same coin. The more water we extract from the ground, the more our water quality deteriorates. This is because a higher concentration of toxic contaminants exist deep within our aquifer – particularly Arsenic and Fluoride, the two most prevalent chemicals in our water supplies. With the increase of industrial scale agriculture in our region, unsustainable overexploitation of our groundwater has driven the water table down from a couple dozen meters in the 1950s to more than 200 meters (~650 feet) in recent years. Today, new wells sometimes exceed 500 meters (~1,650 feet) in depth as the groundwater levels continue to drop by a staggering 2-3 meters (6-10 feet) per year, some of the most overexploited groundwater in the entire world.

Illustration: Representation of our aquifer depletion and the increasing depth of well drilling.

Arsenic and fluoride are invisible and odorless and thus impossible to detect without expensive testing equipment or until people start showing irreversible physical and mental damage. Some of the health effects more prevalent are dental and skeletal fluorosis (teeth get permanently stained and bones become brittle), kidney chronic disease, learning and developmental impairments in children, skin lesions, and different types of cancers. For these reasons, we launched more than ten years ago – in partnership with Texas A&M University, Northern Illinois University, University of Guanajuato, and other national and international institutions – a watershed-wide effort to test the water of hundreds of community and private wells in our region, allowing us to map-out the real extent of water contamination. The results only confirmed that the contamination issues were not limited to a few rogue cases, but were in fact the indicators of a major public health and environmental crisis.

In 2013, together with some of our earliest and most important grassroots partners like CUVAPAS and SECOPA, our water quality data, along with witness testimony on the health impacts, were presented in front of the Permanent People’s Tribunal, an international human rights ethical body, that produced the following statement:

"Given the seriousness of the cases reported regarding overexploitation and contamination of surface and groundwater, and its impact on people and ecosystems, it is recommended that the Mexican government...declare [the entire Upper Río Laja Watershed region] an emergency zone due to the environmental and health risks."

Places like San Antonio de Lourdes, a mere 50 minutes north of San Miguel, is one of the archetypical communities of our region suffering from both of these issues. The community’s well collapsed twice within the span of a few years, leaving hundreds of families without any water access for more than a decade. Even worse, community members regularly went to neighboring agricultural fields where they were “gifted” water from the owners. When we tested those agricultural wells, we uncovered fluoride levels 15-20 times higher than the Mexican and World Health Organization limits for fluoride and more than 6 times higher those limits for arsenic.

Caminos de Agua has worked with both El Fraile and San Antonio de Lourdes, as well as more than 140 other rural communities in our region, over the years to help confront these issues through Rainwater Harvesting and water treatment programs. However, there are hundreds of more communities in our region, and tens of millions of people across the country, who need solutions immediately. We will continue to explore this reality in the coming weeks.

In Part 3 of our Series next week, we will explore The Consequences of our water crisis in greater detail, including the impact on public health and local economy.